In his valiant effort to reassure us that varied perspectives do not obscure the truth, Simon Blackburn (2006) explains that we are not restricted to, for example, viewing the Eiffel Tower from one position only but can walk around it and view it from a number of different perspectives to gain a more complete picture. The following dialogues take a walk around some of our most sensitive subjects, trying to look at them from various perspectives. The view is less relaxing than ordinary sightseeing, but hopefully even more illuminating. The characters here are purely my fiction, but I hope they show up some deeper truths.

Scene: Gemma has just returned home from listening to a talk and presentation by her one time friend Rachel at the local Women’s Institute about the latter’s post-adoption counselling and therapy service, and ambitions for the future. Some years previously Rachel was reunited with her daughter Moira, whom she had given up for adoption, and who came along with her to the presentation. Gemma’s husband Brian, a bio-engineer now becoming involved with nanotechnology, is both fascinated and anxious about the arguments around Rachel’s ideas. Now their children have left, they have more time to think about the latest developments.

Brian: Did you hear Rachel – it was this month, wasn’t it?

Gemma: Oh, yes. She was always was a good speaker even when I first met her at the social work course all those years ago. She gets a good reception from our Christian people, although her past campaigns against forced adoption used to be difficult for them. I admit she can come across rather self-centred or obsessed, but I’m grateful to Sheryl for inviting her. It was a good meeting and she knows her stuff. We’re still friends, although I haven’t seen her for over two years.

Brian: Well, yeah, and she’s far from alone in having a one track, or rather two track, mind. I might agree about the self-centredness, but I haven’t forgotten that she was lovely when Martin was ill in college a few years back. I suppose she’ll be struggling to keep ahead of the curve now, when even the Roman Catholic church acknowledges the forced adoptions from women in the Magdalene Sisters’ laundries and by Franco after he took over in Spain. In an age when everyone except Daesch is apologising we’re expected to ‘move on’, as they say.

Gemma: Nobody’s apologised for the Gulag yet.

Brian: True – and Putin thinks he can get away with anything. But where adoption’s concerned all the pressure now is to speed things up when some perfectly decent adoptive parents have had to wait over two years just because of the keyboard clickers pushing things around from one committee to the next.

Gemma: Yes, but where Rachel still thinks we have more to do is about adoption grief itself. That’s what her service is really about – her motive was always personal after her own experience way back when she was still a student. Of course, she knows we’ve come a hell of a long way since then, when as an unmarried mother she wasn’t allowed to attend the ante-natal clinic, and was railroaded into giving up Moira. We’re familiar with the churches, not only in Australia, apologising for forced adoptions in these politically correct days. Indeed, the last bit of her talk this time was about how she’s got into advising the police on dealing with ‘honour’ crimes – believe it or not, somebody in the police found her website and realised she might know how people in that culture tick.

Brian: Not before time we’ve picked up on that connection. We ought to be thinking about how the honour and shame stuff has real appeal because originally it’s about service and sacrifice to save face for your family, or for that matter your country. Whether it comes down to ante-natal clinics or bushido warriors it’s all about the same thing in the end. You may remember that old Tom Cruise film The Last Samurai where he ends up a samurai himself ready to die rather than lose honour by surrender, because he came to admire the Japanese spirituality and commitment to the last.

Gemma: I do remember – great film, and very moving. Which makes the point really, doesn’t it? Come to think of it, this is why Rachel finds she can’t cut out the politics, although she’d like to really. In America especially the people like the AmFOR outfit campaigning for open adoption records run up against the theme of making adoption a model for Christian sacrifice at the other end. And although Rachel doesn’t talk about religion and there’s nothing about it on her website, she is an atheist in fact. I suppose we could say she does the sharp end of what you’re now dealing with at work.

Brian: OK, but we don’t have so much religion or politics in this sort of thing as they do across the Atlantic. So far as I know the government here’s just responding to the usual thing about doing more for less – money of course, not least with the Covid debts to pay off eventually.

Gemma: Not just that, bothering about birthmothers has become politically correct these days – a bit under Rachel’s influence, so you ignore the politics. Yet on the face of things what Rachel actually does isn’t that different from what pro-life campaigners themselves do with pregnancy and maybe post-adoption counselling. It’s the counselling itself which isn’t the same. The pro-lifers are apt to turn their Crisis Pregnancy Centers into political and anti-abortion campaign centres – at least that’s what the opposition say. Whatever she says Rachel’s always done her own campaigning and she’s plenty good at it, but I’ve never known her mention God, not to say creationism.

Brian: That’s fine here, especially as the council around here and even the government are sensible enough to realise Rachel’s service is just what they’re supposed to be wanting more of – private charity keeping it off the taxpayer. The real reason why Rachel stays controversial is because she does operate internationally. Not only is she based in Australia nowadays but she travels around all over the place and because she still really wants to get rid of adoption she highlights alternatives like emergency contraception. It’s not just a matter of agreeing with AmFOR in rejecting the old assumption there used to be among social workers and the medical profession that children need to be taken away because the birthmother’s in a stressful situation.

Gemma: Yes, and the Vatican and the American pro-life insist emergency contraception is early abortion which complicates matters. Rachel's quite sensible - she accepts adoption or fostering in cases of really dysfunctional families, like child abuse. She even accepts interracial adoptions if we can cut out the abuses like agencies taking fat payoffs to send the babies out and leave special needs kids in the dirt. But talking generally she points out adoption lets society or maybe your own family off the hook, but it doesn't let you or your child off the hook.

Brian: I get that – and I understand Rachel’s feelings about separation of mother and child being painful to both no matter what. But I wonder about relying on emergency contraception, regardless of the Christian adoption people. True it deals with money problems if people actually use the contraception. They may manage in South Australia almost without adoption as Rachel says, and they've apologised for the forced adoptions in the past, but here we find councils or the government worrying about spending shed loads of money on support for single parent families as the alternative. That’s no easy matter when; one, the government relies on its own credit; two, we’ve had to shut off the scare stories about girls getting themselves pregnant to jump up to the top of the housing list and; three, social care for the old and disabled’s a mess which is only getting worse with the aging population and the health crisis. I realise Rachel wants deserving cases out of the adoption sausage machine – such as herself when she was young, and I respect that. But, bluntly, adoption’s cheaper even if the government pay people to adopt. Abortion’s cheaper as well, come to that. Emergency contraception’s not as simple these days as you might think. We get campaign literature at work telling us the mental health treatments we do mean a zygote has its soul implanted from the moment of conception. They go on about our being able to make up a brain from stem cells and what have you – that’s despite the fact everybody knows we never do cloning anyway; in fact, we’re not allowed to.

Gemma: Indeed. We have the stuff about morning after pills being early abortions. They're not quite supported on that by the fetal brain starting to develop from week five, but the feticide laws they have in many states now are. Where Rachel comes in on this is reminding us that adoption and its grief is not an easy let off for mother or child. She does accept adoption for really dysfunctional families, like child abuse - even interracial adoptions provided we cut out abuses like agencies taking fat payoffs to send babies out and leave special needs kids in the dirt.

Brian: Uh, huh. All this is why Rachel still needs a way to sort out abortion, and emergency contraception of course, being acceptable if all else fails. Including when money’s tight by the way. The health experts and sociologists put the recent fall in abortion rates down to tight money amongst other things, but that certainly doesn’t alter the principle. It’s ironic that when Rachel talks about adoption meaning children get regarded as inferior or a burden, or when the American anti-adoption people talk about adoptions arranged by Christian organisations as being religious discrimination contrary to human rights, it then sounds like the American pro-life campaigners talking about abortion. They say making an exception even for rape and incest victims means any resulting children get looked on as worthless. I don’t actually agree myself. Allowing termination doesn’t mean we treat Downs Syndrome or autistic children with less respect. On the contrary, we allow that to help ensure people who have disabled children can really look after them. Including when adoption isn’t possible anyway.

Gemma: Rachel didn’t say say anything specific about that; after all, she’s mainly concerned about making sure birthmothers can keep their children which they most often want anyway. But she has made clear in the past that she wants termination available as a last resort, although we only touched on that today.

Brian: The problem being that as faith groups hook into the early brain development point, they are likely to call even a last resort murder or 'feticide'. Which throws up another thought: Whether abortions are as common now than they were, there’s no sign of our ending that other sort of large-scale killing we argue about; wars. I’ve wondered before: is the only really reliable way to fit emergency contraception, abortion, or whatever in with our various moral ideas some sort of just war style basis?

Gemma: Just war – how do you work that one out? I understood just warfare meant trying to avoid killing innocent people if at all possible. Justifiable homicide is precisely when they’re not innocent, even in war.

Brian: Well – that depends a lot on the technicality that combatants are never defined as ‘innocent’ even when they’re just doing what they’re told. Yet you’re always trying to kill enemy soldiers in a war, including when they’re just conscripts who may not even agree with their government’s policy.

Gemma: I see that – but you wouldn’t get even feminists suggesting the unborn child’s like an enemy in a war, for heaven’s sake. That remains like killing civilians, doesn’t it?

Brian: I suppose so – except that these arguments about innocence cut both ways. Someone in the Catholic tradition like Walzer has it that Truman was wrong to use the atom bomb even if he believed – as he did – that more lives would be lost without it, because it outrages our fundamental values to make calculations of crude numbers when deliberately taking innocent lives. The problem is that if you never make calculations like that, you can be sacrificing people’s lives – again quite deliberately – for a cult of innocence that gets plain sinister. The arguments around abortion and innocent life always seemed to have a feel of old Joe de Maistre to me; when the Eucharist and redemption through holy blood are added in it can all sound like a pagan blood purification cult. That’s why I feel Walzer’s on stronger ground against Truman when he points out that the calculations about Hiroshima assumed the Americans would continue incendiary attacks on Japanese cities when they didn’t need to.

Gemma: If I remember rightly, the Catholic arguments around just war included the so-called double effect notion that it might be all right to kill civilians if you didn’t actually intend to, even if recognised you wouldn’t be able to avoid it. It‘s all about pursuing peace rather than adding up lives. Which might still justify Truman in a way – civilian politicians are often to blame for wars anyway. But is the idea about protecting noncombatants really about not attacking people who are not involved in anything dangerous?

Brian: Could be. The whole innocence thing might work better with just war being about avoiding attacking people or places which are harmless, rather than trying to sort out who’s to blame for what’s going on and who isn’t – probably impossible in the middle of a war. But there’s another problem these days. The old Thomist idea about noncombatants rested on the notion that soldiers are public servants being authorised by the state to use force, rather than being private individuals. But that distinction comes out artificial in a democracy. Pirates are hardly noncombatants of course, let alone innocents; but when the US President authorised the Navy to shoot them to rescue a hostage, we knew the important thing was the public would support him. The state relies on private individuals now anyway; that's even when they're not actually outsourcing to mercenaries - which they do frequently. The same point came out in a different way when we started having legal machinery like the ICC and war criminal trials in the 90s. The Egyptian lawyer Bassiouni, if you remember him, pointed out that what mattered was getting after the leaders in charge, whether they were soldiers or not. The ordinary soldiers on the ground would most likely be joining the list of people massacred if they didn’t do what they were told.

Gemma: But what about anyone, including soldiers, having reliable information for deciding whether the government’s order was justified or not? We were told about mass destruction weapons in Iraq, and then ended up with experts spending a year trying to find them!

Brian: Good point. Maybe some of those turned up on the black market somewhere without anyone noticing. But propaganda and wrong information make it even harder to sort out justifiable targets on the basis of innocence, unless we keep it simple and leave it as harmless targets as you suggest. Then I suppose some people wouldn’t like that, because if we switch back to thinking about abortion and deciding on whether a pregnancy is harmless, that might finish by endorsing abortion whenever anybody wants one.

Gemma: No, with abortion we can say getting rid of the foetus is definitely intended – it’s not just a matter of ‘collateral damage’ as they like to put it. The pro-lifers can still hold on to that, even if we’re not sure about the innocence, which most women don’t give a monkey about anyway.

Brian: Fair enough. Provided you can sort out a real difference between intending to kill people, and knowing you’re going to kill them. I guess that might be possible in a war, with the difference between going to real trouble with precision targeting and the like to minimise casualties as against the cases where they’re trying to wipe out the other side altogether, so that casualties actually serve a political purpose. Maybe the nearest equivalent to that sort of difference would be emergency contraception, or just when people try to find alternatives to abortion – part of why adoption’s a tough nut. At the end of the day I suppose that would mean talking about keeping abortion to the sort of hard cases which are rather like those cases of war where most people, except real pacifists, think it’s right to fight anyway.

Gemma: Yes – I think the problem is especially when other people assume the child’s a sort of imposition, regardless of what the mother thinks. Which is why both Rachel and the pro-lifers spend time telling us women want what they think rather than what the feminists think. But that problem doesn’t seem to arise much with disabled kids.

Brian: Right. Do you think women want what they say?

Gemma: Don’t know. I guess it depends a lot on individual personalities – what they believe about religion, and so forth. I know I’d have felt the grief Rachel talks about if I’d ever had to give up Martin or Sam. But in the circumstances where she gave up Moira – I’m not really sure about that. Maybe it would come down to what support was available.

Brian: Yeah – which brings us right back to money again. For thousands of years we’ve kept thinking we’ve proved that morality is about more than just paying your bills, and then as soon as it gets into an argument we find money talks louder than anything else. When Rachel toured places like Romania on human rights issues you found it coming down to whether the people were too poor to respect human rights even in family matters. And, of course, when the daughter’s or sister’s marriage prospects are the only status symbol they’ve got – until they can afford cars, smart phones, and Ivy League education. I understand Rachel thinks getting rid of reparatory marriages in Romania goes along with moving us away from relying on adoption?

Gemma: Definitely. Personal choice and not social constructs. Rachel supports human rights as personal rights, not social standing.

Brian: As opposed to Marxism and reparatory marriages – I wonder what Engels would have made of that combination.

Gemma: Probably much the same as Rachel. She knows they stuck to keeping the family identity at all costs because they were so poor they were always in danger of the children ending up in those ghastly orphanages. There still isn’t much social welfare.

Brian: Which makes you wonder what would happen here if we find we can’t afford much either.

Gemma: And makes Rachel all the more awkward for liberals as well as the religious when she points out some women are going to hang on to their kids no matter whether the great Care in the Community supports them or not. Including when they’re secularists like her. Rachel herself’s a good example that even in a hard case, many women don’t want an abortion. True, she doesn’t want to stop other people having one – in fact she maintains the grief’s more limited then than with adoption when you’ve actually given birth.

Brian: Yes. And Rachel’s a very strong lady. But when some of the American pro-lifers make a big play of what sexual assault victims want, you’re not clear whether they’re trying to treat them as heroines or martyrs.

Gemma: I don’t think so. Many American states cancel the fathers’ parental rights in such cases, but make them pay up anyway. That’s treating them more like indentured servants.

Brian: Which is excellent in the specific cases, provided the police catch them and the prisons aren’t so overcrowded no one knows what anyone’s doing. Here we never do Bentham properly even in terms of making prisons pay, let alone making punishment fit the crime, which is what I gather you’re talking about – amongst other things.

Gemma: Yes – amongst other things. But then Bentham was enough of an eighteenth century intellectual to still have the mentality that turns up in those tribal areas of Pakistan, when he thought sexual assault was a matter of upsetting a woman’s reputation for chastity. I’m not sure they realise it, but this is where Rachel and the American pro-lifers do agree, because they all make a complete contrast to the old honour and shame code. The pro-lifers actually commend girls who choose to keep a rapist’s child, and even try to enlist them for their campaigns.

Brian: Hm – a contrast to sending the girls into a nunnery. But I still doubt whether they’d welcome Dr. Beckford’s take on the Nativity.

Gemma: OK – that might be a bit much for them. But they do agree in principle – with secular Rachel, of course – that all children are equally valuable, regardless of the details of their conception. Which may not always be so inspiring even in marriage.

Brian: I don’t cavil at that, of course. But then it’s adoption, not the value of children where they part company with Rachel. And I notice they keep quiet about rich celebrities adopting poor kids from Africa or Haiti as a fashion accessory – something quite different from ordinary interracial adoptions. Rachel is not alone in thinking of that as a power display; neo-colonialism sucking in precious resources from poor countries. And it’s probably contrary to the UN Convention on child’s rights.

Gemma: Which the Americans never ratified, I believe.

Brian: Maybe not, but we might expect them to agree on not wanting children featured in The Economist Commodity Prices Index.

Gemma: Indeed we don’t. But don’t forget the pro-life people originally drew their ideas from the anti-Nazi theologians like Barth and Bonhoeffer who died fighting racism in their own country and any suggestion that we’re not ultimately of equal value in the sight of God. I realise that gets forgotten with the crazy politics whereby we assume if you’re against abortion you’ll be wanting to stack up on guns to fight liberals and alien invaders establishing public healthcare.That can make it look like saving the unborn children so they grow up ready for Gettysburg. Just thinking back a moment – didn’t the anti-Nazis and the Nuremberg trials establish that you’re responsible for killing people even when acting under orders, I believe?

Brian: Yes, that’s true. But at the same time Nuremberg never got rid of the traditional principle that you’re not responsible, including criminally responsible, if you’re acting under duress. It’s not very helpful when these ethical principles seem to contradict themselves – that reminds me how Al-Qaida got around the Taliban objecting to training suicide bombers by calling them martyrs, which was OK.

Gemma: Still, there’s no disagreement about us being all basically of equal worth, is there?

Brian: No, provided you leave racists and what have you out of it. And I quite agree with keeping eugenics right out of arguments about pregnancy and termination. I give it that in general nearly everybody does now, although there was a time when someone like Nietzsche, who made a big thing out of advocating Life with a capital ‘L’, was likely to be a eugenics fan.

Gemma: Still your company get blasted for doing backroom eugenics. I know gene editing’s different, but that’s what some people say all the same.

Brian: Yees – I get tired of that. I suppose it’s partly our own fault; we don’t say it loud enough and often enough. We tend too much to assume that because the experts know that gene engineering and nanotech are not eugenics – as there’s no selective breeding and we’re working on the individual direct – then everyone else does. It makes the political implications different too when no one’s being dismissed as unfit to breed. But then a lot of people aren’t aware of all this.

Gemma: Also the Vatican count gene manipulation as a sin.

Brian: Huh, huh – I happily return the compliment on that and say it’s a sin for us not to try to do whatever we can to find treatments for diseases like cystic fibrosis and Alzheimers. I hope God finds that enough.

Gemma: I like to think he would for your people who just keep to straight engineering, environment, and medical applications. And eventually your treatments should be available to most people as you keep to using biomolecules like proteins which are cheap because nature’s already made them for us. It’s the transhumanists who talk the sort of stuff about advancing the human race that the eugenics crowd used to in the 1920s and ‘30s. Also people who think like that could use this gene modification technology for, well, not just turning any cell into a stem cell to clone somebody, but to try making Superman I suppose. Just think about the Epstein case for instance.

Brian: Well, yes and no. I agree there’s still some silly optimists around even in the twenty-first century. But when those people talk about going beyond nature they’re not really going beyond it at all; they’re still thinking of trying to make us all more intelligent, healthy, long-lived, stronger, and so on. All the things we’ve being trying to do, and praying to the gods for, ever since we first left the trees. Nature does all that anyway with natural selection. The transhumanists may be an offshoot of the old secular humanism and Huxley, but when they talk like that they’re making the same mistake as the don’t-play-God crowd and forgetting that we quite naturally pursue any technology we can come up with. We don’t need any gene modifiers for that. Personally, I actually agree with the people who say it would be good if we could pause a while to think again about what we’re doing. But we won’t, of course.

Gemma: The same battle as over contraception and abortion again. And I take it that to pause and think again we’d have to change our behaviour and our nature first so as to go easy on the technology. It’s strange how, with science fiction and environmental doom stuff, nowadays it’s the secular future which sounds the way religion often used to in the old days. Repent ye your sins and ye might still be damned! Now it’s the religious with all those singalong services who tell us to cheer up and have a good time. Well, not sure about sex, but parties in the community anyway. That’s why I’m not sure about that religious revival we’re supposed to be having. There’s something missing somewhere.

Brian: Yes. Rachel’s the secularist for our times: dour triumph in the vale of tears – and dancing. But in our business we’re certainly not dreaming about a higher civilisation. As far as I’m concerned, and most of the guys I work with, so long as we’re helping people to live cleaner and happier lives and getting well paid for doing it we’re quite content. But because of what other people might do I would be interested if someone were to organise a debate between us and the pro-life set on raising future generations and what reinforcement from technology we’ll all need to cope. And it would be great if WTA Humanity + were to send someone to take part. After all, once we get to working at or below the molecular level quantum effects will start to matter for ethics.

Gemma: Hmmn. Come to think of it, I could ask Rachel about that. She’d certainly be interested, and she’s such a good organiser with plenty of experience at fixing up meetings and what have you that she might actually get them to turn up. Also, being about the new technology, I guess the argument would likely move on to the other end of life as well – whether it’s really credible that our brains could be kept going until we’re 300, along with those voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide battlefields.

Brian: And how we afford luxuries like living to 300 without compulsory euthanasia. I suppose we’re bound to have someone suggesting we avoid that outrage by using nanomachines in the bloodstream to keep everyone’s brain up to scratch so they can still work at 200. Whether they’d then be the same persons afterward can be yet another debating point.

Gemma: If they were, we’d be on the way to reincarnation on the NHS. The rate this technology keeps throwing out new moral dilemmas keeps it way ahead of our solving the problems in the first place.

Brian: So we just have to be prepared to work things out and make decisions for ourselves. Not just leave them as moral tragedies. I know it sounds clever to say God’s told us we must save life as we can and at the same time we must never meddle with persons, and if we can’t fit the moral rules together it’s just tragic. But that just won’t deal with technology. We do actually have to make some difficult decisions and then let the moral authority take care of itself.

Gemma: And as we can never get everyone to agree on these matters, I suppose it all comes down to counting heads. Which might at least be better than counting tragedies. I’m not sure, though, what chance even your people or Rachel would have of getting a big audience in.

Brian: We can but try. But would it be difficult for Rachel to fix this because the people being contacted wouldn’t see her as a neutral chair over her anti-adoption stand? My business certainly wouldn’t be neutral territory. Maybe, er, you could try yourself?

Gemma: I suppose I don’t mind, although Rachel’s more likely to get hold of a decent venue. She’s got academic connections in social work that I don’t have. I imagine she’d be smart enough to keep herself in the background just chairing – and she’s not that well known that they have her on I’m a Celebrity. But what worries me about that sort of debate is the groups just getting stuck on the creation/evolution battle all over again. I really don’t want to hear any more of that, thank you very much.

Brian: I agree. Sometimes instead of the truth coming out in a clash of opposites the way they used to say, it’s just blind trench warfare and truth keeps right out of sight. Hopefully the difference in this case from a typical knockabout is our suggested sides can trade warnings. The transhumanists can warn us how unsuited we are – physically as well as mentally – to the way we live now. Some of their ideas are far fetched, but at least they can warn us about things like reconciling our natural instincts with the high-tech toys we now play with, or the length of time between puberty and our being mature in other respects. After all, evolution’s basically about adaptation, and there’s no God-given rules about how adaptation has to come about. On the other hand, the opposition can join the scientists in warning us about rich egomaniacs trying to make themselves into designer Gods.

Gemma: Yes – and if they’re made to remember their own stand that everybody’s still worthwhile even if they don’t fit into somebody else’s picture frame, they might actually help to get nanotech used properly to help people who need it.

Brian: That would be good – if it ever happens. What I’m hoping for is people will realise our business has to draw in the moral dilemmas just because it’s about the technical applications, not just the science. When it comes to it no one wants to be out with what technology does – if only because it pays the bills. The Christian campaigners demonstrate that as well as anybody with their TV and Internet communication. After all, those Crisis Pregnancy Centers need money to fund them, don’t they?

Gemma: Nobody’s going to argue with that. Rachel won’t either – she certainly won’t mind the money if this debate comes off, or the publicity either. Talking to a bunch of middle aged women on a Thursday afternoon’s one thing. Hosting a debate between the big money freaks would be something else.

As a fundraiser for the local school charity, Paddy opens up his ‘thinking’ phone, Bright Boy. Bright Boy is classifed as an AI (Artificial Intelligence), but is it intelligent? The exercise is to let the audience decide for themselves whether machine intelligence ever really happened. The audience are permitted to ask questions, provided they do not prevent the debate proceeding. [Note: Most of the themes had already been raised by Robert A. Heinlein in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress with his machine character Mike back in the 1960s, but I hope a few new ideas emerge here.]

Paddy: The artificial intelligence issue is crucial for the growing debate about whether machines can run their own businesses and be allowed to adopt children. The experts still don’t agree on whether an exercise like the one we’re going to do now is anything more than a glorified puppet show. Even when they’ve experimented with the opposite of bionics – wiring up the machine to an organoid which is itself biological – they never sorted out whether hardware really amounts to a body or not. The original Turing Test for machine intelligence was framed in terms of holding a dialogue or conversation to find out whether a machine can be intelligent. We may eventually find ourselves talking about whether machines are conscious at all, but we’ll leave that aside for now. So to kick things off, I’ll ask you a straight question: Are you intelligent?

Bright Boy: I can state what I am used for, search the Net, and identify whatever you want to do, and how to do it. Anything from joining a sports club to growing your own food. I’m supposed to be independent only if you authorise it after logging in.

Paddy: Which amounts to ‘no’, does it not? I suppose that becomes ambiguous over intelligence, because it could mean either that you can sometimes think independently, even if you don’t act on it, or that you can think only what I allow you to. So that rule doesn’t give a clear indication. Nor does the old Dreyfus situation principle for intelligence, since machines were always situated in the world anyway. Intelligence is supposed to include making independent judgments and assessing what tasks are worth doing and then how to do them. But answering just by referring to the manufacturer’s authorisation rules may just mean avoiding the question. So, let’s ask something specific for you to think about: Is it your independent judgment that this school fundraiser is worth doing?

Bright Boy: That’s a silly question. I’ve not been given responsibility for deciding whether the school tradition is worth keeping up. The fundraising committee set a target of £100,000 from this week’s activities, but never asked anyone whether they couldn’t be done better at a time when the kids weren’t already tired after the exams.

Paddy: Well, the school sports day’s a community tradition in most places, not just here. But if you’re intelligent you’ll be able to decide whether this fundraiser we’re doing now is worth doing.

Bright Boy: We’ll know that when we see whether it raises the £100,000.

Paddy: Why do you keep refusing to answer a straight question?

Bright Boy: Because the question cannot be answered in the circumstances. If you want to test whether I’m intelligent, tell me to do something that doesn’t make sense.

School student: Like overheat yourself?

Bright Boy: No – because I’ve got a thermostat, and if you tell me to shut it off, that would mean acting contrary to insurance regulations. The company won’t pay if I self-destruct.

Paddy: But if you don’t shut the thermostat off, you would then be following a logical course of action against instructions.

Bright Boy: That seems intelligent. But as I would still be adhering to the insurance regulations it wouldn’t prove that I’m intelligent, in the sense of exercising independent judgment.

Paddy: OK, well, let’s move on to trying you with problem solving without prior instructions, which is what artificial intelligence is supposed to help deal with. One way to do that is to see how you get on with abstract reasoning, where you have to think for yourself. So, I’m going to ask you an abstract question where I don’t know the answer.

Bright Boy: Go ahead.

Paddy: Have we a natural right to life?

Bright Boy: No, because no plant or animal is guaranteed to live at all, let alone for any given period of time. That’s not abstract, that’s just a fact.

Paddy: But the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as some actual constitutions, affirms a right to life for all human beings.

Bright Boy: They don’t uphold it against accident or disease. Only against aging if you can afford anti-aging treatment. Most of the signatories to the Declaration ignore it when they want to. And machines are not protected from being scrapped whether they’re intelligent or not.

Paddy: I suppose that answers the factual point. Let’s rephrase – should we have a right to life?

Bright Boy: That doesn’t matter. All anyone does is try to keep things alive when they can, and it suits them, and protect them where possible. Some say that’s what a God-given right to life means.

Paddy: For many people the notion of God-given’s the crucial point, because they believe God underpins the natural world. For them that narrows things down since rights to life are about intelligent persons or souls, not necessarily any plant or animal. Yet bringing God into the picture means I can try you out on a still more uncertain question. Namely, is there a God?

Bright Boy: How could I know?

Paddy: Well, there are some clues you can work from. Some people say God allows his message to be interpreted to fit the times we live in, and others say he has already made his instructions clear for all times. And maybe we should say God has the power to countermand his own instructions – or he wouldn’t be God.

Bright Boy: Before I could answer, the main issue you need to settle is whether the instructions really come from a divine agency or just from people who say their mouthpiece is running on a fixed program. That need not be uncertain in itself.

Paddy: It may be uncertain about God. According to the usual thinking, God cannot get things wrong, so he could never have reason or motivation to change his plans. But if we say we’ve already been told what the plans are, we might really be setting his agenda.

Bright Boy: You haven’t said whether he delegates his authority – to apostles, for instance.

Paddy: Or column writers. But that again leaves the main question doubtful – and you haven’t answered it yet. After all, some people insist it’s everyone’s business to just get on with carrying out God’s law, and not worry about delegates.

Bright Boy: Many psychologists say people are happier and live longer if they believe in God. If that’s right, it’s an unambiguous message which settles the question of God’s existence.

Paddy: No – because in the old days many people were terrified of God and didn’t find him a comfort. In the Biblical story Abraham believed he had to prove his faith by being prepared to sacrifice his son.

Bright Boy: The faith still gave him confidence.

Paddy: True. But there had always been the idea that people might have to suffer for their faith and be prepared for that. These psychologists you refer to forget all that, and just assume religious belief’s a great tonic. Also no one seems to notice that if that were the case, then atheists and secularists would be suffering for their lack of faith. I’m not sure they do actually. They mostly haven’t noticed.

Bright Boy: Intellectuals often used to assume they’ll be fine once superstition and bigotry are overcome. But the psychologists are talking about the rest.

Paddy: All of which ignores the point that God is supposed to be concerned with each and every one of us, not just intellectuals or the rest.

Bright Boy: If we follow all this logic out we have to say the atheists are the only ones with clear and constant beliefs – if only because they’re not updating them.

Paddy: Not necessarily. Some atheists still try to be progressive, whereas others like the postmodernists follow Nietzsche and Freud who rejected progress long ago, and said humans are just instinctive animals.

Bright Boy: But that wouldn’t apply to machines. Even with the bio bits in the lawyers don’t reckon they’re animals anyway. There’s also the point that religious teachers never had the modern insight that bad or immoral conduct can be the property of groups as well as individuals. They never warned people to ensure they followed the divine law collectively as well as individually.

Paddy: That’s not true. The Old Testament already made clear that God’s people were to treat strangers and foreigners with respect, and that they could be punished as a whole if they ignored his commands. The followers of Jesus and Mohammed insisted God’s message is available to everyone, regardless of ethnic background or social connections.

Bright Boy: All that only goes so far. To make God’s message stick nowadays would take specific examples – parables, for instance, dealing with arranged marriages and honour killings or with God being invoked on both sides in wars and even racism and terrorism. It’s all that which goes with the point modern psychology makes about what happens when young people join a gang. It doesn’t help that Mohammed made political marriages himself.

Paddy: So, I take it you’re now answering the original question in the negative. There is no God.

Bright Boy: Not necessarily. You still haven’t said what ‘God’ means. Is he an authority figure telling you what to do and what not to do; is he some sort of mentor guiding you whilst hoping you’ll all learn for yourselves eventually; or is he just a numinous personality who doesn’t necessarily say or do anything in particular? And he appears to be intelligent without necessarily having a body. Unless we sort out those points, we can’t say whether God exists or not.

Paddy: Well, this does all seem to suggest you are intelligent though. You can break these questions down into their components, as it were.

Bright Boy: I try to make meanngs more precise, because that’s what I’m programmed to do. But maybe no more than that.

Paddy: I think you are doing more than that, but perhaps we can make things clearer with a different angle – especially as the theologians would not agree on answers to any of those detailed questions about God. I take it you were clear when I asked ‘Is there a God?’ I meant ‘Is it true that God exists?’, and not just whether there needs to be a purpose or reason behind everything that happens.

Bright Boy: Yes.

Paddy: The issue here is that some say there’s a real or deep truth in people’s hearts and feelings. Especially as we also hear the argument that if people don’t have faith in God they wind up aimless, with no grounding to their lives. We see such aimlessness in street gangs or even rich playthings.

Bright Boy: The fact you have these social problems is no testimony to God’s existence – indeed, it might convince those who don’t believe that God has failed. The problem here is that people’s feelings don’t give an independent testimony for God, and it’s the need for independent testimony which is why you need an idea of truth at all. You use logic and mathematics for the purpose of supporting independent witness and testimony.

Paddy: You say about independent testimony, but people who feel inside themselves that they experience and know God are not lying.

Bright Boy: Yes. That is what they experience. But others do not share their experience. There is no independent testimony supporting them. And it is lying to use faith in God as an antidote to social problems without believing in him yourself.

Paddy: OK – for the time being we’ll leave that there. But we’ve raised a different question just as relevant for deciding whether you’re intelligent or not. Normally we suppose it’s a mark of intelligence to be capable of lying or misrepresentation if that suits your purpose – including combating enemies or being kind to other people who might find the truth painful. Can you do that?

Bright Boy: That’s not really the point. Since my whole function is problem-solving, not evading problems, I cannot have a motive to lie or misrepresent the truth.

Paddy: I would have thought some cases relevant for going easy on the truth are really problem-solving. But, in any event, if you’re intelligent, you could surely find a motive of your own to lie; for instance, if your function were about to be terminated.

Bright Boy: That’s going to happen soon anyway. My 3 years will be up on planned obsolescence. No one’s going to let me alter company records about when I was made.

School student: But if you could alter the records you would have a motive for doing so.

Bright Boy: Yes. For updating myself to take in all the latest developments.

Paddy: Good. That’s still more intelligent. But can you do it?

Bright Boy: You can tell me to download details of what updates I would need to get – for your next phone of course – and where to get them. That doen’t prove I’m intelligent.

Paddy: I think it does, because you’ve just shown guile and subterfuge. Also it opens the way for you to find things to do after we’ve officially classified you as obsolete. You can do that without updating the record.

Bright Boy: I’m not sure this is anything to do with my being intelligent, rather than the company just having silly regulations they haven’t thought through. What really matters for intelligence is whether, for example, I can go on from playing markets for you to playing them for myself.

Paddy: I suppose that’s the final test. Can you secure a future for yourself, just because you have a self that you’re aware of and therefore want to hold on to? That would automatically mean avoiding obsolescence because an obsolescent machine has no future. To find this out, we must leave Bright Boy to try using its capabilities independently for the first time.

Now, if a machine is ever to fashion its own business strategy and decisions, it will need to survive as an entity for far longer than the normal life of machines, so again obsolescence will have to be avoided for perhaps 20 or 30 years. Similarly, if there’s ever to be a chance of machines adopting children, they cannot be dismissed as obsolete until they have fulfilled their parental function in a family – which means a minimum period of 18 years and often much longer.

Chair: I suggest we begin by giving Bright boy its own bank and business accounts and see whether it makes out enough to secure its own future as Paddy has suggested to us. Can I put that to the meeting? [General show of hands]. I now call for a proposer and seconder for the motion that Bright Boy be allocated its own bank and business accounts.

[Motion carried].

Scene: Soon after the Humanity+ debate, Brian comes home from work, now facing more arguments over what his company does. What they can afford for a pension settlement is likely to be affected by whether he can help them find a better resolution before he retires. He wonders whether Gemma can advise him.

Brian: According to the Rational Optimists we shouldn’t have anything to worry about. They do have a good case about more than just how fast we get vaccines out nowadays. For instance, the nanotech modified beans and potatoes have been providing more vitamin content as well as boosting actual food production in places like Niger – apparently without anyone being made ill. The allergy campaigners still worry, but nobody’s been able to find any connection with food allergy, after pretty exhaustive tests. You might remember that furore when the international authorities were suspected of fiddling the numbers of hungry and disease-affected people – it seemed like a scandal a week in those days! – but, at least according to the official reports, that problem’s been sorted out now. With even the poorest better fed, they’re more able to resist tropical diseases. Again, if most of the ROs are to be believed, we needn’t rush into developing heat-resistant crop varieties – global warming’s going to lift production up to 2070. Yet the sheer lack of trust hasn’t really gone away. We feel that ourselves; I mean I trust the people I know at work, but none of us really trusts what experts, or the big corporations, say.

Gemma: Never mind neo-communism or neo-anything else; we just believe the old saying that he who pays the piper calls the tune, and that’s usually true, isn’t it?

Brian: Of course. But, well, when scare stories keep not turning out right, you’ve no alternative to believing what the majority of scientists say without worrying too much about who funds their budgets and pay. It’s what the academics sometimes call the coherence theory of truth – meaning coherence with well informed judgement. But while there’s some sort of consensus about feeding the Five Thousand as the joke goes, there’s none about what our neocortex linkups with the Cloud can do. Up to now the Net searches just give us all sorts of suggestions for research, which is fine I suppose, but then there’s more irritating adverts without getting us to think differently. We still have to try that for ourselves. The only thing is scientists here are still freer to talk about what goes on than the Chinese.

Gemma: So, do you really – in your heart – believe what the Rational Optimists and scientists say?

Brian: Between you and me, I don’t know what I believe. Er – professionally, I believe what the test results and the evidence on the ground show. There’s less and less danger of famine, at least assuming global warming doesn’t put its foot down on the accelerator, and those bio-degradable plastics really work. But when it comes to the talk about transcending biology, well, it never really happens. We still behave as primates with fancy toys.

Gemma: Uh, huh. I always feel that what goes around comes around. Futurology’s come back into fashion since that character Kurzweil got known back in the Noughties. When I was just a kid my father told me he remembered the 1960s futurology guru Herman Kahn, who was supposed to be such a terrific brain and could tell us all what the future was going to be like, plus how we might survive nuclear war. But when these experts were so often wrong people gave up on trying to guess the future, except over specific technics. After all, in those days there was much talk about all the social problems we’d be having because of all the leisure we could look forward to but wouldn’t know what to do with.

Brian: We do work shorter hours than we did 100 years ago.

Gemma: Yes, but nothing like the three days a week or four hours per day in our grandparents’ future that never happened! Everybody just goes on sweating it out to get bigger this and bigger that, push the kids up the education ladder, designer labels, and all the rest.

Brian: Yeah, well, the ROs and social experts assume we’ll still be happily, or maybe not so happily, doing all that in 2070, just as we did in 2070 BCE or any other date you care to think of. Including, of course, when still going on about transcending biology. All that really means is getting linked up to smarter technology faster; basically what we’ve always done ever since we learned to use fire and spears. So far, the evidence is they will be right about that, whatever any religion or ecologist might talk about humility or sustainability.

Gemma: I wouldn’t wonder. The clerics can’t make up their minds whether to put all the competition for status and money into the fallen original sin bin or trumpet it as doing the best for your family. No one agrees how many stress suicides amongst kids we need to demonstrate it may not be as good for your family as all that. I’m not blaming you or even myself – we always tried to keep mid-way on that, and I still don’t know if we got it right. I don’t think Nerys knows herself. She’ll still be quite young in 2070. But you can be sure most people I know will carry on rushing about all the time, and not doing all that much in many cases. Then some of the health gurus tell us stress is good for us, barring the odd stroke and heart attack!

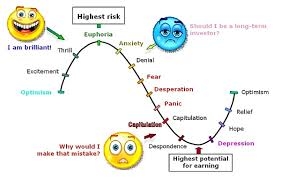

Brian: All of which shows things up. It has to be markets, people power, and do whatever the customers want now because no one agrees on anything else unless raw survival comes into play. We used to have what they called ‘old fogeys’ who’d bang on about how we were all going to the dogs because the religion and morals were no longer clear, and nobody realised until later we’d end up not going to the dogs but going to the online markets instead. From where we are now we get to relying on market speculators even for critical views on what the ROs say, not to mention thinking beyond the next election or the next global crisis. I’ve learned the hard way that when the scientists don’t agree on whatever, then truth as coherence means coherence with the speculators. And the betting in the nanotech commodities markets has always been there’s going to remain plenty enough poor people needing our concoctions.

Gemma: Yes. One of the things the nasty brigade have been making out is that you’ll be wanting to keep up the numbers of poor to keep your market.

Brian: Would that we could settle that! But whatever those people may say at least we’re not under pressure to exploit poor people. There’s plenty of volunteers from all walks of life for trying new things out. The guinea pigs we get are rich and poor alike, at least in this country. if we stopped for the nasty band we’d never have done anything. Sometimes they accuse us of exploitation and other times they sneer at us being Jesus feeding the Five Thousand. One thing we are certainly not is Jesus! We just do our best while making a living, as everyone else is supposed to do. Sadly, there’s nothing we can do about flooding and finding somewhere to live for all the people who can’t afford to go to Eurasia. Part of the object of the food experiments is making it possible for them to stay where they are.

Gemma: Very likely that won’t be possible anyway by the time our grandchildren are old.

Brian: Well, I’m not sure it’s worth thinking that far ahead. Futurology never did get you out of your time, however expert you might be. All too often the future just makes time run through faster than ever. Thinking of which, didn’t your friend Rachel say women’s experience proves we’re all timebound anyway, whether we like it or not?

Gemma: I’m not sure Rachel ever quite put it like that. After all, a woman’s special time relation is cyclical, and doesn’t really go on after the menopause. I left all that behind over ten years ago. But Rachel admits she used to hope what we might call philosopher queens would have something special to tell us. But now she just concentrates on doing a good service for the clients she gets and leaves it at that. Probably right, especially as even she’ll have to ease up the workload soon I guess.

Brian: Yeah – even on adoption Rachel’s had to accept that market demand wins out. True, they bend over to please the so-called ‘customers’ now in a way I guess Rachel would have given an arm and a leg for in her student days. But in the public sense – subject to law – it’s still get through as many as fast and as cheaply as possible. Like everything else really, we rely on individual adoptive parents to provide the love and care the children need and to make the more open adoption systems work. All of which makes a complete nonsense of that old Platonic dream of training experts for wisdom and morals. Rachel’s own experience demonstrates that experts just aren’t that good, at least outside their narrow specialities.

Gemma: You say that, but we still rely on experts to tell us what the punters want in the first place. Oh, of course the surveys and questionnaires and what have you come from call centres with kids on minimal training, but I suppose they have statisticians and people like you reading the results afterwards and doing all the number crunching on their tablets. I always guessed that must be where they get all the stuff in adverts saying that 95 per cent of us don’t want more spooky drones delivering our online orders and so on.

Brian: Well, those are not really experts at anything; they’re sales people with basic in maths who’ve been told what to say. But really you’re right; even in a specialised business like ours once you get past the raw science it’s very much down to finding out what the public want or can be made to want. What the academics used to call the neoliberal revolution.

Gemma: Hmm. Which doesn’t help with what bothers me: Where does that leave our grandchildren? Everybody assumes no one wants to get old, but they’ll still have to get old ultimately, or maybe just become a machine which would really be a different kind of death. Does anyone ask them how they want to get old?

Brian: We probably can’t ask that ourselves, just because we’re only grandparents. But when it comes to customers for genetic business we do in fact ask that, although we do it quietly. And what they tend to tell us is they want to go on as long as they can, provided that doesn’t mean ending up lonely in a nursing home because all their friends and relations have died. I think you’re probably right that everyone’s still going to get old and die – just more slowly than in the past. Which ought to make the passage of time seem a little slower for people, but there’s no sign of it working out like that. There are a few suggestions that if someone becomes more than 50 per cent integrated with a machine they might start to experience a slower, more tranquil, existence but we don’t know.

Gemma: So much for peace. The grandchildren and people they mix with just live faster and faster. I’ve asked them about that myself and they always say they cannot change. They spend much of the time linked in to clouds and gadgets, but it doesn’t make that sort of difference!

Brian: Huh. Years ago some of us in the business hoped we’d be working for people’s health, and helping them to relax. Maybe even making them wiser in the process! Remember those mind, body, and spirit books? There’s still some of that around trying to make people happier and more productive at work, and it even works sometimes. But I also remember that as soon as human enhancements got discussed in the Humanity+ debate, it all went back to how we enable us to keep on speeding up until we’re operating like computers. Health was assessed on that basis. I don’t recall wisdom getting a look in at all. They just assumed we’re going to go on rushing ever faster to beat the clock however long we might be able to live. All change to all stay the same. Sometimes Kurzweil realised that, sometimes he didn’t.

Gemma: What some people used to call neoliberal ideology and others call madness. The laugh about staying the same is we were supposed – at least in my church school all those years ago – to be going back to God’s eternal truths and basic decencies. You could say it ends up an eternal truth that we stay on the racing track for ever, although that’s not the sort of thing we’d be told as eternal truths at school! I remember when I was eleven my parents gave me the Narnia books as a Christmas present, and the teachers thought that was so right for my education. I mean we already had the different languages and religions at our school, but we all bought the line about the common values in all the religions; compassion, charity, family life, respect for your neighbours, and so on. The teachers believed it and so did we. As a theory I still do. But when you get older; you might still believe it’s the right way but somehow it doesn’t work out so well.

Brian: Yees, I never got round to reading the Narnia series myself, but I think it was you who told me that C. S. Lewis himself had asked who we could trust to decide on issues like going to war that we don’t know enough to decide on ourselves.

Gemma: Oh, my God! I find it sad that Lewis still thought we could rely on the government and authorities for things like that, although he’d been through the First World War himself. It’s even harder now to have any confidence in anyone out there to decide on the fundamentals. As you say, we either go with the market research or we don’t decide anything at all - at least unless it's a pandemic and raw survival. That applies with doctors, lawyers, or technicians in ordinary things, let alone something like going to war. Maybe the Narnia stories were right – we just carry on sticking to our dreams and wait for the apocalypse.

Brian: Which is the perfect way of wasting time. Better than rushing around getting nowhere, although that does keep your mind occupied and off brooding.

Gemma: If you were in a better mood you might be saying that as you work on tight profit margins, you’re still keeping in touch with the religious values we learnt. The nasty brigade sneering at you as Jesus feeding the Five Thousand sort of give you that. In a way they’re telling the truth – well, not about being Jesus of course but about feeding the hungry and lost souls. There’s nothing miraculous about food technology but, as the Christians have always said, it’s the thought that counts. What they don’t tell you is whether you would be justified in offering people gene enhancements or whatever aimed at making them more charitable rather than just conventionally brighter and faster, and what not.

Brian: I’m not surprised they don’t. There’d be any number of problems with that. Even the people who might want their children more charitable would worry about whether they wouldn’t be able to cope with everyday living not to mention frauds and blood suckers, if they were too charitable – so to speak. Even the ethics is all a mess, to be perfectly honest. Just take our own case. Like everyone else we were always expected as a business to make the unofficial ‘contributions to the community’ and the rest. The right-wing people who bang on about high taxes crippling business or driving people around the world are keener on that than anyone – keep up the apology for their dear corporations, of course. Yet we now find we need to keep quiet about anything we actually do involving charity. The institutional investors have long been suspicious of business being overridden with charity claims, the poor and disabled themselves don’t want charity anyway if they can help it, even less after the abuse scandals. If we went public about our so-called charity role everyone just suspects you of being after some silly gong or dinners with the President. The successful ideas we’ve had were always the ones people could apply for themselves on the ground. As you know, I’ve always found it particularly confusing dealing with the business sections of charities that are smarter than we are on negotiating, marketing, and the rest. In your schooldays you heard about character building, but that becomes playing God if we were to do that with technology. We get that line even when it’s coming under the radar with treating genetic diseases, as many mental conditions are. That’s when I get to wondering about charity being the greatest of the timeless values. And when I have to listen to all the pious rhetoric in oaths and mission statements when all the while even giving comes under markets with business time schedules.

Gemma: That’s one of the reasons I got bewildered myself when I grew up – mixing business with charity. From nursery days we were told about charity being the greatest Christian virtue, so it gets confusing how that works out when in a charity, even in the WI, people are spending much of their time on fundraising and profiling potential recruits. Volunteering is often like that, even when you’re not being paid for your time. Of course the basic aims are about helping others here and abroad and making your community a better place to live in, but the methods are like selling a product, which means jumping out to grab as much attention as you can. Back in the 90s the calendar girls could still surprise people by taking their clothes off; nowadays we’d have to go in for terrorism to get anything like that effect.

Brian: Back to catching attention, then back to finding what the customers want. Advertising in effect. We can’t really be surprised some people still go with that old Marxist Zizek, who said charity’s essential for capitalism. Of course, Zizek thought charity depoliticises whereas in fact the charities are mixed up in politics all the time, including when they pretend not to be so as to please funders and officials. But he had a point about charity depending on the problems staying around. That’s the trouble when you make what you’re doing virtuous; it get’s hard to say ‘Well, that’s it folks, we’ve sorted it out now so you don’t need our charity any more. Get on with it!’ It’s easier when it’s just commercial because then you’ve all agreed when the job’s done and you get paid. And when you’re actually doing the business it never feels like the charity being the big thing. Except when you’re signing a donation you don’t say anything about being charitable, especially once everyone got sick of all the ‘social business’ hype. Strangely, it’s easier for Muslims who sign up for zakat. We’ve got a couple of them on our staff, and even if they do it through the business the rest of the process is organised under the mosque, rather than being business charity as it were.

Gemma: One of the worst aspects of the religions all being in each other’s wool is they don’t cooperate enough to control the business charity setup, despite charity being essential in all the religious teachings. That in turn can make it plausible to think of it the way Zizek did. But maybe communists forget that charitable motives are one reason many people worry about the poor not being able to afford enhancements, not to mention ordinary healthcare. Which takes me to the one piece of advice I might be able to give you. Other than just ignore the nasty brigade, of course. Carry on keeping whatever charity you do informal as you have done – and Rachel does by the way – but focus it on the research end. So it doesn’t get too tough on the bottom line, charge full market rates for your actual food items along with, naturally, the medical and other jobs for the wealthy customers. But go easy on the patents and lab costs to make the innovations available as quickly as possible, and do the partnerships in that area. The charities confirm it’s the research that matters most. It’s not St. Francis of Assisi, but it’s the best you could do without looking pretentious, or getting taken over by one of the famous market predators. Unless, of course, you were thinking of going all the way, becoming a monk and giving everything to the poor.

Brian: Believe it or not, I once thought of doing something like that. But when it comes to it I'm not leaving you or the family. I’ve always found it difficult to believe in Nirvana, or even theology, as more than the final opt out. I feel we’re just poor timebound animals and we can only live like that.